If you went snorkeling in the Mediterranean and were confused to spot a sunny-side up-egg floating around the ocean, you’re not the first! But you’re unlikely to have come across someone’s lunch – it was probably a fried egg jellyfish.

Find out everything you need to know about the strange Mediterranean fried egg jellyfish, including its natural habitat, diet, stinging capacity and much more.

| Name (common, scientific) | Fried egg jellyfish, Mediterranean jellyfish, Cotylorhiza tuberculata |

| Family | Cepheidae |

| Spread | Mediterranean Sea |

| Habitat | Close to the surface in shallow waters |

Fried egg jellyfish appearance

Before we start: don’t confuse the Mediterranean Cotylorhiza tuberculata with the large, cool-water jellyfish Phacellophora camtschatica. Both are often referred to as fried egg jellyfish, but the Phacellophora is much larger. It sports a rounder bell and much longer tentacles.

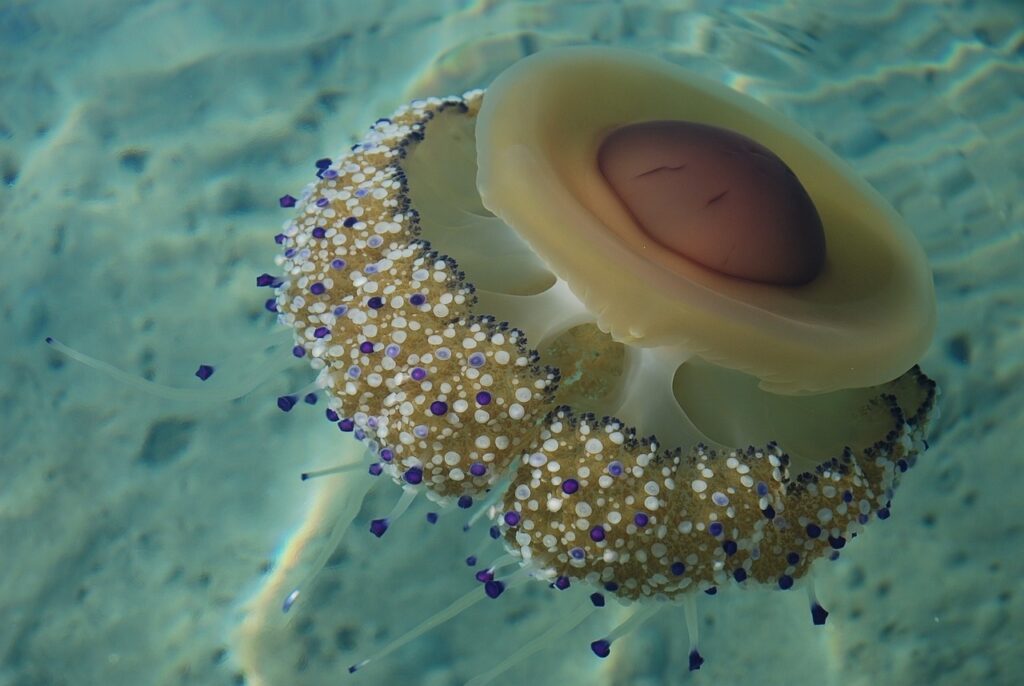

As for C. tuberculata appearance, there’s really no escaping it: the common name says it all. The fried egg jellyfish has a flat-topped, off-white bell with a bright orange, smooth central dome, making for a look that’s extremely reminiscent of a cracked egg. As with all jellyfish, the dome can contract and pulse, allowing the jelly to swim.

Below the egg-like bell is a bunched mass of branched mouth-arms with white or blue tips. Out of this bunch also dangle a few longer tentacles, which are blue-tipped.

At a maximum diameter of 40 cm/16″, these jellyfish can grow quite a bit bigger than the average egg.

Did you know? It’s possible to spot the difference between male and female fried egg jellyfish by looking at their mouth-arms (the bunched part of the tentacles). Females will often be carrying partially developed embryos in them for protection. These embryos give a reddish color.

I think a video is best suited to show this wacky ocean inhabitant in all its glory:

Fried egg jellyfish habitat

As mentioned in the introduction, the fried egg jellyfish is naturally found in the Mediterranean, including the Aegean Sea and Adriatic. Recently, it has even made its way into the Sea of Marmara in Turkey and other areas where it wasn’t present before.

In the species’ natural habitat, you’ll mainly see it pop up during summer. As a result of the warm waters, huge blooms can occur, with thousands and thousands of jellies appearing seemingly out of nowhere in early summer. You’ll mainly see them cruise along just below the water surface in coastal areas. By late autumn, they all perish.

Fried egg jellyfish masses can be bothersome for tourists and local businesses. Sometimes there are so many that it makes boating and fishing impossible. In countries where blooms happen, local municipalities will often attempt to remove the jellies.

Did you know? The reason the fried egg jellyfish has been able to spread into the Sea of Marmara and other new habitats is thought to be warmer sea temperatures as a result of global warming. As jellyfish take over, plankton levels can drop, which can pose a problem for the overall health of the ecosystem as other plankton eaters go hungry.

Planning your next snorkel trip?

Fried egg jellyfish diet

The fried egg jellyfish is not a “killer” jelly like some of its highly venomous cousins. Although it has a big bunch of tentacles at its disposition, its sting is pretty weak and it only consumes small creatures like one-celled organisms, larvae and copepods. Its “favorite foods” are Spiroplasma, a genus of bacteria.

Aside from the prey it can catch while floating around the ocean, the fried egg jellyfish has another trick up its sleeve (or rather, its tentacles). This species carries zooxanthellae, specifically endosymbiotic dinoflagellates belonging to the family Symbiodiniaceae. Now in normal English: these are single-celled algae that live in the jelly’s tissues.

Zooxanthellae are pigmented, and they’re actually the reason for the jelly’s bright blue tentacle tip color. That’s not all they’re good for, though. Their main job is to photosynthesize in order to produce energy for the jellyfish.

That’s why the fried egg jelly tends to live close to the surface: deeper waters are too dark for proper photosynthesis.

Did you know? It’s eat or be eaten… and in this case, the fried egg jellyfish is considered a delicacy by the loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta).

Fried egg jellyfish facts

Do fried egg jellyfish sting?

Jellyfish blooms can be wildly annoying if you’re just trying to get some snorkeling time in before summer ends. Trust me, I know: I used to spend a lot of time in Ibiza, and avoiding the stinging Pelagia noctiluca (mauve stinger) was impossible without a full wetsuit and gloves sometimes!

However… I’ve got good news for those finding themselves surrounded by a mass of hundreds of fried egg jellyfish. Unless you’re allergic, in which case touching it can cause some irritation, Cotylorhiza tuberculata does NOT sting.

You might get a mild itch, but there’s no need to panic at all if one of these jellyfish touches you. Feel free to have an up-close and personal look if you come across one; they’re incredibly fascinating to see.

All aboard the jelly express

Fried egg jellyfish can have a negative effect on local ecosystems by decimating plankton populations, thereby taking food away from other species. However, they also have their good sides! For many young fish species, these jellies form a sort of natural nursery.

Baby fish, like the horse mackerel, will flock to jellies like this one and use them for shelter. They eat any bits and pieces that the jellyfish isn’t able to move from its tentacles to its mouth quickly enough, and they’ll also take a bite out of their host itself from time to time.

Life cycle

Although they’re considered rather “basic” organisms, jellyfish life cycle is actually pretty complex. The life of a fried egg jelly consists of no less than four different stages.

It all starts when adult jellies start dancing the horizontal tango in late summer to early fall, with the females receiving sperm from the males through their mouth-arms.

After fertilization, things go a little like this:

Stage 1: Planula

Planula are tiny larvae that start their life in the female’s protective appendages. They make their way into the world once they’ve developed hair-like cilia, which they can use to move around.

Planula eventually settle on the seafloor to move into the next stage, preferring a hard substrate.

Stage 2: Scyphistoma

Also referred to as polyps, Scyphistomae develop less than 2 weeks after the Planula settles. They look nothing like adult jellies at all, instead consisting of a stalk, a cup-like body (calyx) and tentacles that wave around in hopes of catching small foodstuffs. A Scyphistoma is mostly sessile (unable to move) and will eventually acquire zooxanthellae.

As it hangs out on the seafloor, a Scyphistoma reproduces asexually by dividing itself into more polyps. This usually happens through a process called budding, in which a new polyp forms on the stalk of an old one. The new polyp breaks off, swims for a bit and then settles down.

The most important factor for polyp survival is temperature. They like things nice and toasty, which is also why the biggest fried egg jellyfish blooms occur in years with mild winters and warm, long summers.

Stage 3: Ephyra

Each of the individual polyps produced by the Scyphistoma eventually morphs into an Ephyra, abandoning its stalk. These Ephyrae reach a maximum size of around 1 cm (0.4″) and are free-swiming, but they’re still very basic.

Stage 4: Medusa

Finally, the jellyfish has matured into the form we’re familiar with. It will quickly reach its adult size continue living for a few more months at this point.

At the end of summer, light levels start going down. As a result, the photosynthetic zooxanthellae in the jellies’ tissues begin dying off. It has less energy to move around, making it unable to catch enough food in its tentacles. This is what eventually leads to the demise of a fried egg jellyfish.

Sources & further reading