The ocean is like an enormous puzzle full of fascinating pieces, and jellyfish are some of the most intriguing. It’s hard to ignore them, and indeed, we should pay them the attention they deserve. Proper jellyfish identification can be life-saving!

For snorkelers, diving into the underwater realm often brings encounters with jellyfish. While the majority of species pose no threat to us, a select few pack a venomous punch that can cause serious harm and, in rare cases, even prove fatal.

Understanding jellyfish and their dangers is essential to make the most out of snorkeling. Let’s have a look at what they are exactly, and then discuss 10 jellies that you should know how to identify and avoid.

What is a jellyfish, anyway?

Jellyfish are cnidarians, a group of animals that also includes sea anemones and corals. Their most notable feature is their cnidocytes, specialized cells that contain organelles called cnidae. These cnidae are responsible for the jellyfish’s infamous stinging ability. Upon contact, the cnidae release tiny harpoons, or nematocysts, that pierce the skin and inject venom.

The venom of each jellyfish species contains unique bioactive compounds. Research into these compounds is ongoing, and some early findings actually suggest various potential pharmaceutical applications.

The jellyfish’s lifecycle is equally intriguing (and wacky). They begin life as polyps attached to the sea floor, eventually budding off into free-swimming medusae (the jellyfish we know). These medusae can reproduce, forming eggs.

The fertilized eggs develop into larvae and attach themselves to the substrate, forming a new polyp. This cycle, known as metagenesis, is a fascinating aspect of jellyfish biology that has helped these animals to inhabit oceans for over 500 million years.

All jellyfish are predators. However, not all of them pose a threat to us humans. In fact, although plenty can deliver a painful sting, the vast majority are considered not to be dangerous unless you happen to be allergic. Take the funky fried egg jellyfish: you can touch every part of it, including its tentacles, without issue.

There are roughly five types of jellyfish that are potentially deadly to humans, plus a few more that can cause serious trouble. Below, we’ll have a look at these “deadliest jellyfish”, how to identify them, and how to avoid getting stung.

Jellyfish Identification: 5 Potentially Deadly Jellies

This league of silent assassins, while small in number, can have a significant impact. Although deaths are still very rare, you’re unfortunately not likely to forget an up close and personal encounter with these species any time soon.

Meet the ‘Potentially Deadly Jellies,’ species that have been known to cause human fatalities. From box jellyfish to the deceptive Man o’ War, they’re as fascinating as they are dangerous.

1. Australian Box Jellyfish or Sea Wasp (Chironex fleckeri)

A fixture on lists of the world’s most venomous creatures, the Australian Box Jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri; also known as Sea Wasp) may not look like very much, but it’s very much a creature you’re best off avoiding. Some sources list it as the most venomous animal in existence!

Primarily found in the waters around Northern Australia and throughout the Indo-Pacific, this Box Jellyfish is mostly active from October to May, during what is appropriately called the stinger season.

The name comes from this jelly’s bell, which is generally cube-shaped or box-like, with tentacles hanging from its four corners. This unique shape, coupled with a sophisticated sensory system (including a set of 24 eyes) allows the Box Jelly a degree of maneuverability in the water that many of its cousins lack.

With its unusual agility, nighttime activity, strong preference for shallow waters and strong attraction to light, it’s a prime candidate to ruin your night swim.

Data about encounters with these potentially lethal creatures can be alarming to read. According to reports, as many as 10,000 people are stung by Sea Wasps on a yearly basis in the Philippines alone.

In Australia, about 100 serious envenomation cases are recorded annually, with over 70 of these requiring hospitalization. Over the past century, this Box Jellyfish has reportedly claimed over 60 lives in Australia alone.

Did you know? An antivenom for Chironex fleckeri stings exists. According to research, it isn’t perfect, but still a good addition to healthcare professionals’ jellyfish sting treatment arsenal.

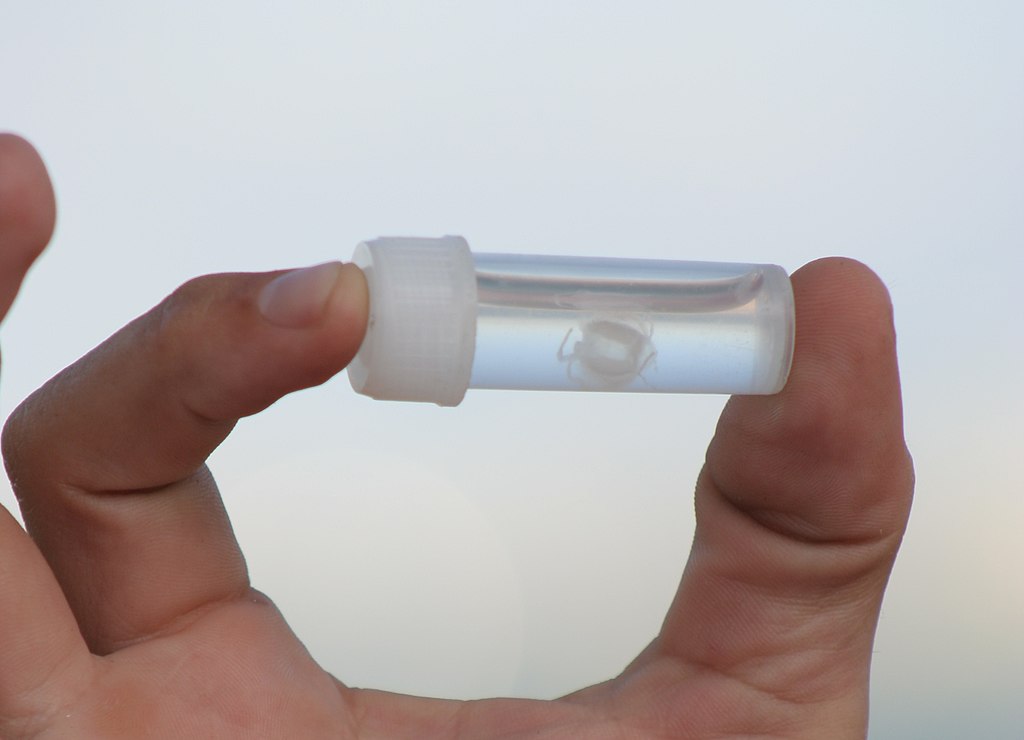

2. Irukandji Jellyfish (Carukia barnesi & Malo sp.)

The Irukandji Jellyfish, which comprise Carukia barnesi and a few species in the genus Malo, also frequent Australian waters. As with the Box Jelly, their peak activity time is during the warm stinger season. Interestingly (and somewhat alarmingly, if you ask me), Irukandjis have apparently also been spotted in locations as varied as Japan, Florida, and the British Isles.

First described in 2007, these cnidarians are proof that lethality is not necessarily proportional to size. Its bell is a mere cubic centimeter (that’s 0.4”!), yet it harbors tentacles that can stretch to a staggering length of over a meter (~3ft).

The jelly’s venom is potent enough to induce the severe Irukandji syndrome. This condition has the potential to cause all sorts of nasty symptoms, from hypertension and debilitating pain to nausea and, in extreme cases, cerebral hemorrhage.

Because their size and translucence make them almost invisible, the Irukandji does pose a threat to swimmers and snorkelers. In Australia alone, it is estimated that there are about 50-100 Irukandji stings each year.

The good(ish) news? While excruciating, an Irukandji sting is rarely deadly, with only two fatalities reported since 2002. Interestingly, one of the species (Malo kingi) is in fact named after its only known victim.

3. Habu-kurage or Viper Jellyfish (Chironex yamaguchii)

Yep, another Chironex jellyfish makes the list. This cousin of the Sea Wasp is called the habu-kurage or Viper Jellyfish (Chironex yamaguchii) and is a common danger around Okinawa, Japan and the Philippines. It was actually thought to be a different box jellyfish until relatively recently, with the species being officially described in 2009.

Like other box jellyfish, the habu-kurage is an elusive marine threat thanks to its small size and transparent body. Its venom, unfortunately for us, is brimming with potent cardiotoxins,. It can disrupt heart muscle cells, potentially leading to rapid cardiac arrest depending on where a person is stung.

Habu-kurage jellyfish are named as culprits in several fatal stinging incidents, so there is good reason to suit up if you go for a swim. In fact, the actual casualty count may be higher due to potential underreporting in rural or isolated areas.

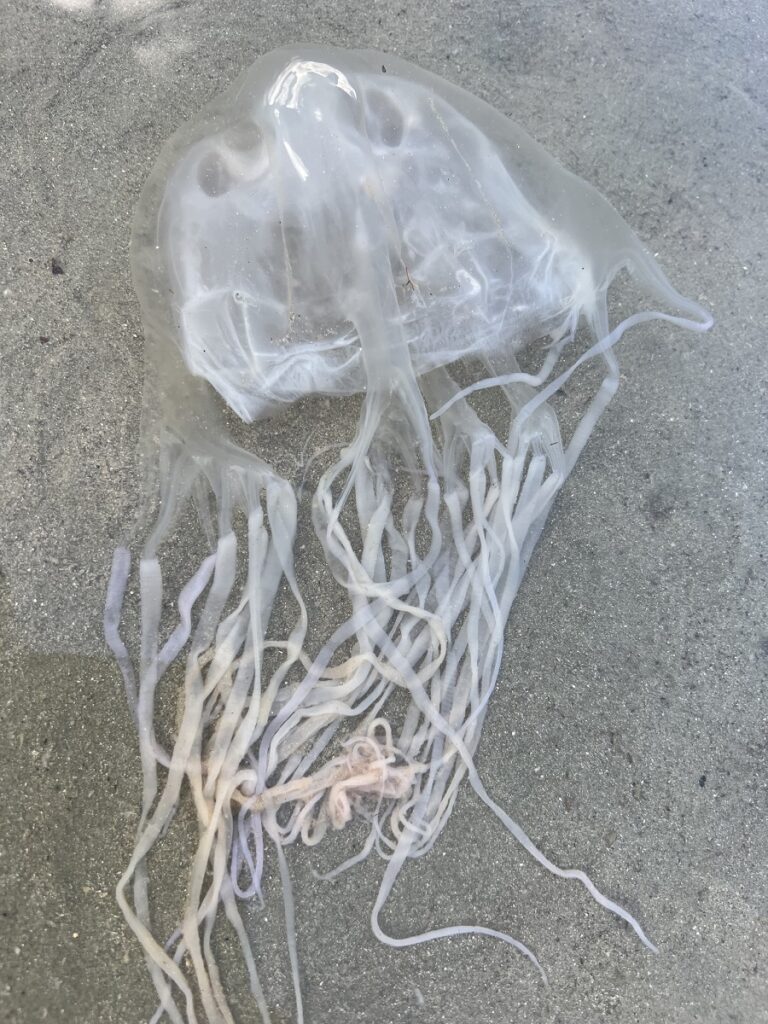

4. Portuguese Man o’ War (Physalia physalis)

The Portuguese Man o’ War, Physalia physalis, is a rather deceptive oceanic creature. It’s not actually a single organism, nor is it technically a true jellyfish, although it looks enough like one that I’d like to include it here.

This wacky floating creature is in fact a complex siphonophore, which is a fancy word for an assemblage of specialized individual polyps functioning as a collective. A bit of a marine voyager, it sails the world’s oceans using a gas-filled bladder as a sail, making its geographical range extensive.

Although its venom isn’t as potent as some others on this list, a Portuguese Man o’ War sting is still intensely painful. It causes nasty welts and, on rare occasions, serious cardiovascular issues.

Despite an estimated 10,000 to 30,000 incidents annually in Australia alone, serious injury or death from a Man o’ War encounter is exceptionally rare (though it can happen). This is thought to be largely due to immediate and effective first-aid responses. However, allergic responses or cardiac arrest do sometimes claim lives, so let’s just avoid this one, shall we?

5. Other Box Jellyfish Species (such as Chiropsalmus quadrigatus)

While the aforementioned Chironex fleckeri and Chironex yamaguchii tend to grab most of the limelight, there are a good few other species within the box jellyfish family that deserve attention.

One of these is Chiropsalmus quadrigatus, another small but lethal jelly that inhabits the warm coastal waters of the Indian and Pacific Oceans. The aforementioned habu-kurage was actually long thought to be a C. quadrigatus.

Most commonly encountered in the Philippines, Vietnam, and other Southeast Asian countries, C. quadrigatus has a particular affinity for shallow waters and river mouths, especially after rainfalls. This behavior increases their threat during the post-monsoon period, when these environments are most likely to form.

Like its better-known cousins, C. quadrigatus boasts a box-like bell shape and dangling tentacles full of venomous cnidocytes. This venom is powerfully neurotoxic and can cause significant pain, cardiac distress, and in severe cases, death.

Although comprehensive statistics on stings from C. quadrigatus and other lesser-known box jellyfish species are hard to come by, regional reports suggest they contribute significantly to the estimated tens of thousands of jellyfish stings that occur globally each year.

Jellyfish Identification: 5 Potentially Serious Stingers

While not typically associated with human fatalities, our ‘Potentially Serious Stingers’ are still well worth avoiding. These jellyfish can transform a fun snorkeling tour into a distressing trip to the ER. Their stings may not claim lives directly, but they can lead to severe harm and life-threatening complications, particularly if you’ve got allergies or pre-existing health conditions.

Without further ado:

1. Lion’s Mane Jellyfish (Cyanea capillata)

The humongous Lion’s Mane Jellyfish, aptly named for its sprawling tentacles, holds an impressive record as the largest species of jellyfish on the planet.

This marine titan prefers the frigid, boreal waters of the Arctic, Northern Atlantic, and Northern Pacific Oceans as its home. During the warmer summer months, they tend to drift closer to the coastline, raising the alarm for swimmers and snorkelers.

A sting from this jelly can trigger a range of symptoms, from localized redness and intense pain to systemic complications like muscle cramps and respiratory distress. While deaths from these stings are very rare, individuals with allergies or underlying health issues should be extra careful.

2. Stomolophus meleagris (Cannonball Jellyfish)

Nicknamed for their ball-like shape, these jellyfish are predominantly found in the warmer waters of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. While their sting is not deadly to humans, nor usually a major cause for concern, it can still result in a very uncomfortable rash. Cardiac problems have also been recorded.

Their unique trait? Cannonball jellyfish are often used as a food source in certain Asian cultures and are considered a delicacy. When swimming, though, as with all marine life, it’s best to admire these creatures from a safe distance and avoid direct contact.

3. Pelagia noctiluca (Mauve Stinger)

A light in the dark, the Mauve Stinger (also pictured at the top of this post) is a bioluminescent jellyfish often found in the deep waters of the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. However, they’re known to be carried closer to the shore when winds pick up, as well as when they reach the end of their life cycle in fall.

This jellyfish, as its name suggests, has a purple-blue bell. It’s quite beautiful, but unfortunately delivers a painful sting that can result in an intense rash. In rare cases, muscle cramps or cardiovascular issues can also occur. Snorkelers, particularly those with skin sensitivities, should be careful.

The best way to avoid a painful encounter with a Mauve Stinger is to snorkel during daylight hours, when they’re less likely to be found near the surface. This can be difficult during jellyfish blooms, though, as I personally found out while snorkeling in Ibiza one summer! I avoided getting stung by wearing a long-sleeved wetsuit and staying vigilant.

4. Olindias formosus (Flower Hat Jelly)

The Flower Hat Jelly’s beautiful array of glowing tentacles might make it seem more fascinating than alarming. Found mostly in the Western Pacific Ocean off the coast of Japan and Korea, they tend to stay near the sea floor during the day, rising to the surface at night.

A Flower Hat Jellyfish sting, while not typically life-threatening, can cause a painful rash and even leave a nasty scar. Night snorkelers, be aware! Avoiding contact with this radiant but risky beauty is the best course of action.

Did you know? Like the Portuguese Man o’ War, this one’s not technically a true jellyfish. They are quite closely related, though.

5. Morbakka fenneri (Fire Jelly or Moreton Bay Stinger)

Hailing from the waters of Moreton Bay, Australia, the Fire Jelly or Moreton Bay Stinger gets its name from the intense burning sensation that follows its sting. A Box Jellyfish lookalike, this one can be told apart by its stripey tentacles.

While coming into contact with it is usually not life-threatening, it can lead to Irukandji syndrome. As mentioned earlier, this is a condition that can induce severe hypertension and heart failure if left untreated.

Those with existing heart conditions should be particularly cautious. As they tend to dwell in shallow waters, particularly around marinas and off popular beaches, protective clothing and vigilance can help prevent any fiery encounters with the Fire Jellyfish.

Conclusion

The ocean, while beautiful and well worth exploring, is home to several potentially harmful jellyfish species. If you go snorkeling in certain regions, it’s important to understand the risks they pose to avoid unwelcome encounters.

Most stings occur due to accidental contact. Keep your distance and suit up if you go swimming in areas that are known for harboring any of the species on this list. Remember: even though deaths are rare, coming into contact with these jellies can land you in the hospital and ruin a holiday.

Knowledge of different species, awareness of the signs of severe stings, and understanding the appropriate first-aid responses are all vital to ensuring a safe snorkeling experience. As long as you respect marine life, prepare adequately and act sensibly, you can still snorkel.

Remember, these species are as much a part of our oceans as beautiful corals and colorful fish, and their conservation is important. So, as you venture into the sea, appreciate their presence – but try and do so from afar!

Sources & photo credit

Sources & further reading

- Gershwin, L. A. (2007). Malo kingi: A new species of Irukandji jellyfish (Cnidaria: Cubozoa: Carybdeida), possibly lethal to humans, from Queensland, Australia. Zootaxa, 1659(1), 55-68.

- Gershwin et. al (2013). Biology and ecology of Irukandji jellyfish (Cnidaria: Cubozoa). In Advances in marine biology (Vol. 66, pp. 1-85). Academic Press.

- Isbister, G. K. (2010). Antivenom efficacy or effectiveness: the Australian experience. Toxicology, 268(3), 148-154.

- Lewis, C., & Bentlage, B. (2009). Clarifying the identity of the Japanese Habu-kurage, Chironex yamaguchii, sp nov (Cnidaria: Cubozoa: Chirodropida). Zootaxa.

- Munro, C., Vue, Z., Behringer, R. R., & Dunn, C. W. (2019). Morphology and development of the Portuguese man of war, Physalia physalis. Scientific reports, 9(1), 15522.

- Stein, M. R., Marraccini, J. V., Rothschild, N. E., & Burnett, J. W. (1989). Fatal Portuguese man-o’-war (Physalia physalis) envenomation. Annals of emergency medicine, 18(3), 312-315.

- Underwood, A. H., & Seymour, J. E. (2007). Venom ontogeny, diet and morphology in Carukia barnesi, a species of Australian box jellyfish that causes Irukandji syndrome. Toxicon, 49(8), 1073-1082.

Photo credits

- Chironex fleckeri: © Cemone Hedges – some rights reserved (CC BY-NC)

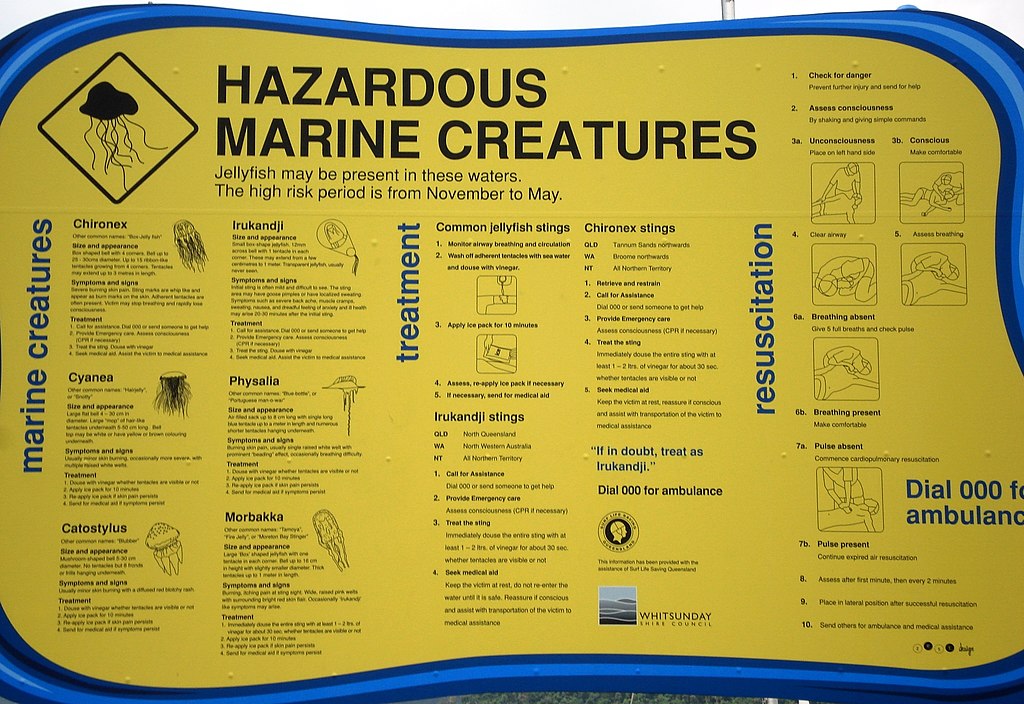

- “Stingers” sign: Genet (Diskussion), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Malo kingi jellyfish: GondwanaGirl 04:29, 6 January 2009 (UTC), CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- “Stingers” sign: Genet (Diskussion), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- “Hazardous Marine Creatures” sign: Genet (Diskussion), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons