Went snorkeling in the eastern Atlantic or Mediterranean and spotted a huge jellyfish? It may just have been Rhizostoma pulmo, also known as the barrel jellyfish or (rather appropriately, in my opinion) the dustbin lid jellyfish.

Below, let’s have a look at everything you need to know about this large jellyfish species, including how to recognize it and whether its sting is harmful.

| Name (common, scientific) | Barrel jellyfish, dustbin lid jellyfish, frilly-mouthed jellyfish, Rhizostoma pulmo |

| Family | Pelagiidae |

| Spread | Eastern Atlantic, Mediterranean, Black Sea |

| Habitat | Open water |

Barrel jellyfish appearance

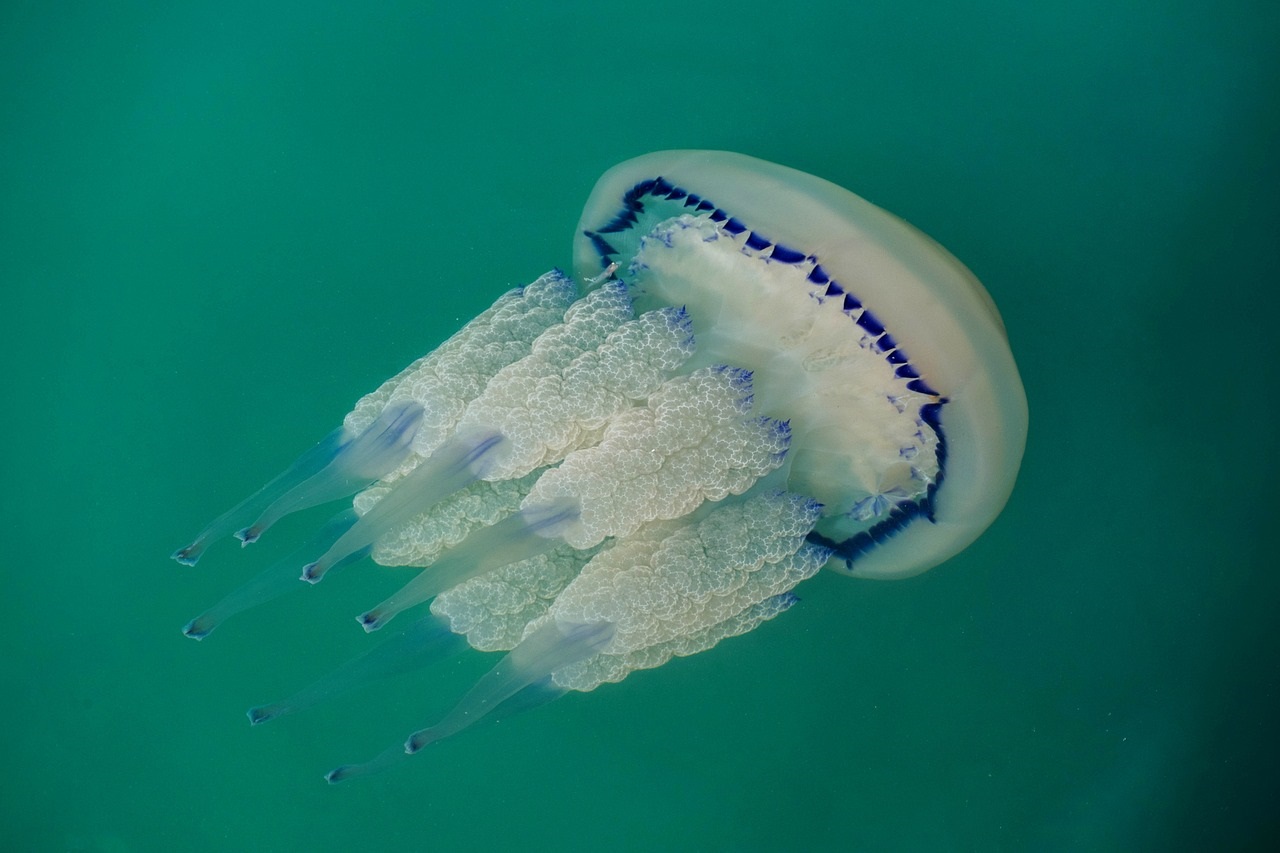

As far as jellyfish go, the barrel jellyfish (Rhizostoma pulmo) could be considered almost pretty. It sports a milky white bell rimmed with dark blue to purplish ruffles. Below the bell are eight oral arms, blue at the top and cauliflower-like in appearance.

This jelly’s most notable characteristic is its size. Its bell can reach 50 cm (20″) in diameter, with even larger specimens having been recorded. Barrel jellyfish weighing 10 kilos (22 lbs) or more are not unusual. Quite a sight to see!

Barrel jellyfish habitat

The barrel jellyfish is naturally found in the eastern Atlantic (mostly northern, but also around South Africa) the Mediterranean (including the Adriatic) and the Black Sea (including the Sea of Azov).

This species is particularly common around the British Isles, especially in the Irish Sea, as well as in the North Sea. Overall, it seems the spread of Rhizostoma pulmo is expanding, as are the numbers in which it occurs every year and the length of the jellyfish season.

Like some other jellyfish species (the fried egg jelly, for example), the barrel jellyfish can cause issues locally. High temperatures, which occur more frequently as a result of global warming, can provoke absolutely humongous blooms. These can be swept to the coast by wind and currents.

In 2021, an extreme Rhizostoma pulmo bloom was recorded in Italy. Apparently, more than 10 jellies per square meter were found in some locations! Spain’s Mar Menor, a large saltwater lagoon, is also prone to being overrun.

Jellyfish blooms cause various issues. They’re not only bothersome for tourists just wanting to do some snorkeling, but can also severely impact fisheries, hydroelectric plants and even the local ecosystem. Due to their weight, barrel jellyfish are noted to cause fishing nets to break!

Barrel jellyfish diet

Its ruffled tentacles reveal what the barrel jellyfish likes to eat: zooplankton and other small bugs. A few studies have examined the stomach contents of this species, finding such meals as:

- Copepods

- Ciliates

- Fish eggs

- Diatoms

- Dinoflagellates

- Crab and shrimp larvae

Many of these are single-celled organisms: Rhizostoma pulmo doesn’t eat fish or large prey.

One special thing about the family Rhizostomae, which today’s subject belongs to, is that they completely lack tentacles. Instead, they have eight (rather than the usual four) oral arms, which feature infinite tiny openings that basically “filter” the food into the jelly’s stomach.

Did you know? It’s eat or be eaten, baby! Jellyfish are a primary food source for sea turtles. Rhizostoma pulmo is a particular favorite for the leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), which has been estimated to be able to eat up to 80% of their body weight in these jellies a day. Impressive, considering they weigh 500 kilos (1,100 lbs) or more. Sunfish also love snacking on barrel jellyfish.

Planning your next snorkel trip?

Barrel jellyfish facts

Sting

The barrel jellyfish isn’t on the list of most dangerous jellies; it’s considered to be moderately venomous, as far as jellies go. If you get stung, there’s generally no need to worry. Still, you can expect discomfort: skin irritation, lesions and ulcers are not uncommon.

If jellyfish are present and you’d still like to go snorkeling, wearing a long-sleeved wetsuit or a rash guard can be a good idea. Bring some vinegar to pour on stings; don’t pee on them or use fresh water. Seawater is alright, but vinegar is really best!

Life cycle

If you’ve read any of my other jellyfish profiles, you’ll know that these invertebrates have rather wacky life cycles. It all starts normal enough: with an egg.

After this, things get weird. A 2011 study describes the full life cycle of Rhizostoma pulmo:

- Fertilized eggs stay with mom until they’ve developed into planulae, which have hair-like cilia they can use to propel themselves.

- The planulae attach themselves to a substrate and develop into stationary polyps (called scyphistoma), which use tiny tentacles to feed on zooplankton.

- The polyps continue to develop. Once they reach a certain size, they can begin to reproduce asexually by dividing themselves (in a manner that’s not unlike propagating a plant).

- The polyp begins to bud. At this point, it’s referred to as a strobila.

- The strobila releases multiple eight-pointed ephyrae, which are basically baby jellyfish.

- The ephyrae develop into medusae: the barrel jelly’s final form.

Parasites

Every creature, including a jellyfish, is its own little universe. The barrel jelly, for example, is home to a surprisingly wide range of (sometimes highly specialized) parasites.

One study found that a whopping 100% of barrel jellyfish examined were infected with lepocreadiid trematodes, better known as flukes. The parasites were present in all parts of the host’s body!

Did you know? Invertebrate parasites aren’t the only organisms that use barrel jellyfish to their own benefit. Small fish do as well! Baby horse mackerel, for example, use Rhizostoma pulmo jellies for safety and as a source of food. They eat zooplankton caught by the jellyfish, and even sometimes consume bits of their host itself.

If you have any more questions about the barrel jellyfish or want to share your own experiences with Rhizostoma pulmo, don’t hesitate to leave a comment below!

Sources & further reading